Recently, I visited the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and explored Alexander Calder mobiles and sculptures in the Elemental Calder exhibit, on view until May 2020. Upstairs, an ongoing exhibit, Approaching American Abstraction, filled the fourth floor with works from the museum’s collection and the extraordinary Doris and Donald Fisher Collection, in a 100-year loan arrangement.

The Fishers, founders of San Francisco-based Gap, Banana Republic, Old Navy and other fashion labels, began collecting in the 1970s to liven up the hallways of their headquarters. They amassed more than 1,000 pieces - now considered one of the most important private collections in the world - by visiting artists’ studios and galleries, and building lifelong friendships with many artists.

The entrance wall to the Approaching American Abstraction exhibit stated:

“Artists use abstraction to push beyond the recognizable world. Whether charting an interior landscape or extracting essential shapes from nature, abstract artworks take us into a new realm of thought, emotion and perception…. In luscious paint strokes, luminous planes of uniform color, and constructions of wood and metal, the paintings and sculptures assembled here both capture these artists’ individual ideas and thinking and offer singular visual experiences.”

Conspicuously missing in the Collection were abstractions using the materials and techniques of photography, which is the medium I work in. SFMOMA happens to have the largest space on the 3rd floor devoted to all types of photography of any art museum in the United States but SFMOMA and most museums continue to segregate abstract photography from abstract paintings and sculptures in exhibitions.

There have been a few exceptions, notably an exhibition last year at the Tate Modern Museum in London Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art, the first show of its scale in which the history of abstract photography was explored alongside paintings and sculptures. This went beyond artists such as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy whose practice included both photography and painting, to presenting artists working in the single medium of phtoography.

Gallery dealers on the forefront are beginning to embrace this concept and I’m pleased that Janssen Artspace Gallery’s “A Modern High” exhibit, opening February 15, 2020 during Modernism Week in Palm Springs, will exhibit nine of my photographic abstract works, side by side, with abstract painters, including the one below.

Playground. Photographic abstract by Steven Silverstein, archival pigment inks on canvas. On view at the Janssen Artspace Gallery in Palm Springs.

© Steven Silverstein. All rights reserved.

In 1930, Alexander Calder, inspired after a visit to Piet Mondrian’s studio in Paris, revolutionized sculpture by suspending kinetic abstract shapes rather than anchoring them as a solid mass with a support base. In 1931, Marcel Duchamp dubbed the first motorized versions of Calder’s sculptures as “mobiles,” a term that stuck. The following year, Calder finalized his designs to derive motion from air currents without motors, allowing free and natural movement that also responded to human interaction - a kind of aeronautical gymnastics.

In doing so Calder created a new vocabulary for modern art. Double Gong (1953) and Fishy (1962) are two of the playful mobiles on display in the Elemental Calder exhibit consisting of colorful boomerangs, spheres, amorphous forms and shapes found in nature, held in suspension by delicate wire and balanced by gravity.

Fishy (1962) and Double Gong (1953) by Alexander Calder.

He carried over a variation of these to Big Crinkly (1969), an aptly named 150” x 97” metal floor sculpture, on view in the terrace just outside of the exhibit room.

It was delightful to see Calder’s use of colors, themes, symbols and shapes in his work continue to amuse and inspire nearly a century after his discovery.

Alexander Calder’s Big Crinkly (1969).

Following Abstract Expressionism, a period in the 1940s and 1950s dominated by experimentation and exploration of personal feelings, abstract artists pushed in new directions, resulting in several divergent styles. These artists favored bright colors, a flat surface without drips and heavy brush strokes, with an interest in how shapes, forms and lines moved, often beyond the limits of the canvas. Styles included hard-edged painting, soak-staining, a continuation of color field painting, minimal painting, and oddly shaped canvases used by artists such as Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly.

After seeing Calder’s and Ellsworth’s work on separate floors, it was clear to me that they shared a visual language. Indeed, I discovered afterward that in January 2019, the Lévy Gorvy Gallery presented the first major exhibition of works by both artists to “explore the visual and personal affinities” between them. Although 25 years difference in age, each had spent their formative years in Paris and met there.

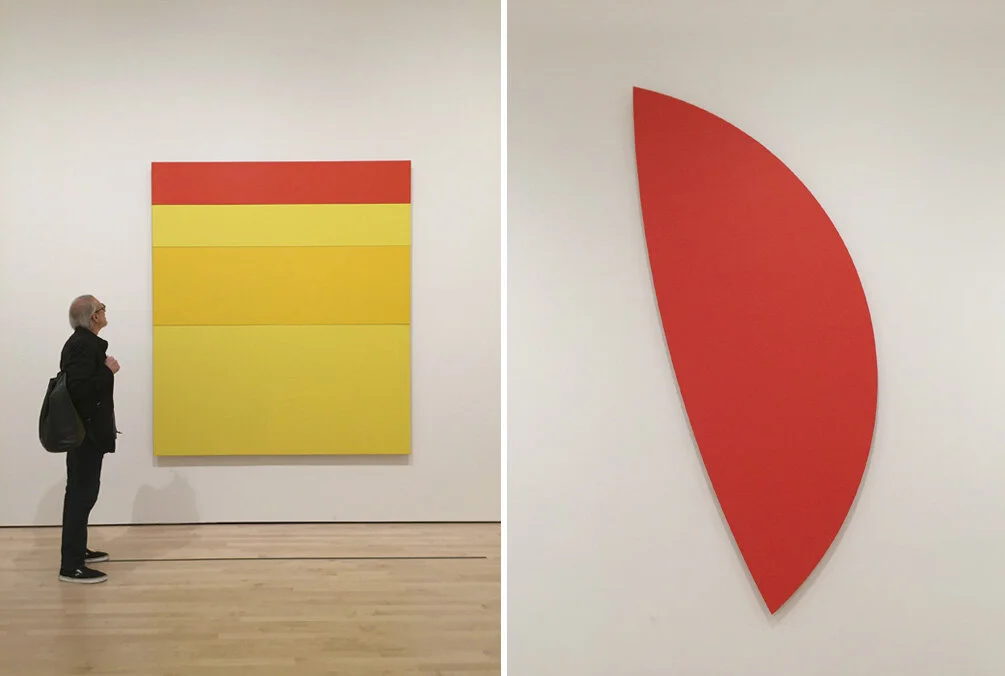

In the early 1950’s, Kelly painted a single vivid color on multiple horizontal panels and joined them together to create a form. Gaza (1956) is an example of this in the SFMOMA exhibit. Eventually, from the 1960s to the early 2000’s, he evolved from rectangular formats to oddly shaped single canvases, some overlapping and abutting one another, planned out and composed before he ever put brush to canvas.

The white walls of the SFMOMA gallery have essentially become the background of Red Green (1968), Blue White (1968), and Red Curves (1996), while playing an interactive role with the intense, mesmerizing slabs of brilliant color in the foreground, filling the room with their presence.

Where’s Silverstein? There he is… viewing Ellsworth Kelly’s Gaza (1956). At right, Red Curves (1996).

Blue White (1968) and Red Green (1968) by Ellsworth Kelly.

A contemporary artist, Suzan Frecon, whose work was donated anonymously to the museum in 2017 (not part of the Fisher Collection), also shares a vocabulary with these artists. In the oil on linen diptych, book of paint version 3, she deploys orb-like forms in two stacked rectangular canvas panels. Interactive in their arrangement, they are made of natural colors found within nature, which she tends to gravitate to.

Book of paint, version 3 (2017) by Suzan Frecon.

Other artists in the exhibit used abstract shapes and colors in different ways. In the early 1950s Helen Frankenthaler developed a technique using thinner that reduced oil-based washes into the consistency of watercolor, soak-staining the paint into unprimed canvas. After Morris Louis visited Frankenthaler’s studio in 1953 and saw her first soak-stain paintings, he was inspired to create vibrant and luminescent, bulbous bands of saturated colors in the extraordinary Untitled work (1959-1960). Louis used acrylic resin to thin Magna acrylic paint, allowing colorful and playful soak-stain forms to explode at the surface of the painting with his own distinctive style.

Untitled (1959-1960) by Morris Louis.

Diverse techniques, along with each artist’s personal vision or expression, determined the outcome of the artwork. But it’s also apparent that a universal mind-think, a shared vocabulary, is also at play that crosses generations. I sometimes produce vibrant symbols, shapes and forms in graphics (as shown above), and among artists who use them, there often is a common denominator. When I recognize that commonality, it’s like seeing an old friend even if we had never met. I know them but I don’t know them. To see these colorful symbols, shapes and forms in person is intense and I can’t express the happiness I felt to see them in other artists’ work.